Aquia Creek Landing, 2846 Brooke Road

Stafford County, Virginia

The Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad was extended to its terminus here at Aquia Landing in 1846. By steamboat and railroad, travelers from Washington, D.C., to Richmond could complete in 9 hours a journey that took 38 hours by stagecoach. In May-June 1861, Confederate batteries at Aquia landing exchanged fire with Union gunboats. The first use of nautical mines (“torpedoes”) in the war occurred here on 7-July 1861 against the U.S.S. Pawnee. After the Confederates abandoned the site in 1862, the Union army built new wharves and storage buildings for supplies. The army burned them in 1863, when it pursued the Confederate army into Pennsylvania. The railroad was extended across Aquia Creek in 1872.

The Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad was extended to its terminus here at Aquia Landing in 1846. By steamboat and railroad, travelers from Washington, D.C., to Richmond could complete in 9 hours a journey that took 38 hours by stagecoach. In May-June 1861, Confederate batteries at Aquia landing exchanged fire with Union gunboats. The first use of nautical mines (“torpedoes”) in the war occurred here on 7-July 1861 against the U.S.S. Pawnee. After the Confederates abandoned the site in 1862, the Union army built new wharves and storage buildings for supplies. The army burned them in 1863, when it pursued the Confederate army into Pennsylvania. The railroad was extended across Aquia Creek in 1872.

Supply Base for the Union Army

Aquia Landing’s location on the Potomac River, coupled with its access to the R. F.&P. Railroad, made it an important supply base for the Union army. Food, clothing and other equipment were shipped down the Potomac River, unloaded here, and sent to the front by train. Recognizing its potential importance to the Union Army, Confederate troops destroyed Aquia Landing in April 1862 and tore up the railroad tracks running between here and Fredericksburg. The Union Army immediately rebuilt these facilities but then foolishly destroyed them upon evacuating the area in September.

Aquia Landing’s location on the Potomac River, coupled with its access to the R. F.&P. Railroad, made it an important supply base for the Union army. Food, clothing and other equipment were shipped down the Potomac River, unloaded here, and sent to the front by train. Recognizing its potential importance to the Union Army, Confederate troops destroyed Aquia Landing in April 1862 and tore up the railroad tracks running between here and Fredericksburg. The Union Army immediately rebuilt these facilities but then foolishly destroyed them upon evacuating the area in September.

Gen. Ambrose Burnside rebuilt Aquia Landing again in November 1862 to supply his army during the Fredericksburg Campaign, adding an additional wharf at Youbedam Point, farther out on the Potomac River. The Confederates destroyed these structures in June 1863 after the Federals abandoned Aquia Landing and marched north to Gettysburg.

In May 1864 Gen. U.S. Grant used Belle Plains, six miles southeast, as his main supply base while rebuilding Aquia Landing. As Grant pushed toward Richmond, he abandoned Aquia in favor of supply depots farther south. The Confederates once again destroyed it after the Federals left. This time is was not rebuilt.

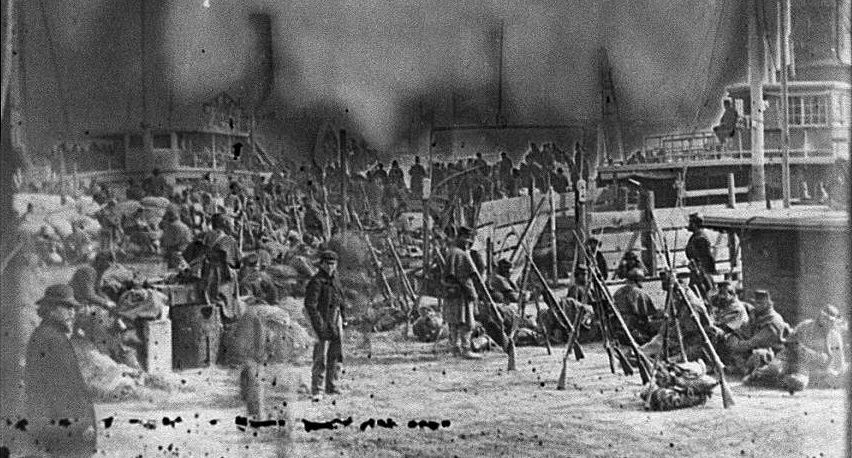

The Union Army used Aquia Landing for moving troops as well as supplies. This photograph shows the Ninth Corps embarking at Aquia Creek in February 1863 en route to Newport News, Virginia.

The Union Army used Aquia Landing for moving troops as well as supplies. This photograph shows the Ninth Corps embarking at Aquia Creek in February 1863 en route to Newport News, Virginia.

When the water at Aquia Landing proved too shallow for deep-draft vessels, Ambrose Burnside constructed a new wharf at Youbedam Point, closer to the Potomac River.

As the Union Army moved south it used tidewater rivers for supply. Aquia Landing, Port Royal, White House and City Point became supply bases for Union bases for Union campaigns.

Steamships, Stages and Slave Trade

Aquia Landing (pronounced ‘un kwyy´yuh’), here at the junction of Aquia Creek and the Potomac River (to your right) was once a vital hub in Virginia’s transportation network. As early as 1815 steamboats from Washington and Alexandria made regular trips here, transferring passengers, mail, and even slaves to coaches bound for points south.

Aquia Landing (pronounced ‘un kwyy´yuh’), here at the junction of Aquia Creek and the Potomac River (to your right) was once a vital hub in Virginia’s transportation network. As early as 1815 steamboats from Washington and Alexandria made regular trips here, transferring passengers, mail, and even slaves to coaches bound for points south.

In 1842, the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad completed its line to Aquia, reducing travel time between Washington and Richmond. The junction here of steamboat and rail marked Aquia as an important place in antebellum Virginia and a major crossroads of the interstate slave trade.

By the 1850s.Virginia was exporting more slaves than any other state. Thousands of them, often handcuffed and packed amidst the cargo, passed through Aquia bound for slave markets farther south. From Aquia, most traveled onward by coach or, after 1842, by train. Some larger groups were forced to walk in chained gangs, or coffles, to destinations as far as 300 miles away.

Early Escape Route

The opening of the rail line to Aquia in 1842 provided opportunity for slaves seeking freedom. In 1848, slaves William and Ellen Craft of Georgia embarked on their dangerous journey to escape. Ellen, born of a slave mother and white father disguised herself as white man seeking medical treatment in the north. William assumed the treatment in the North. William assumed the role of her body servant. They traveled by train, carriage, and steamship from Georgia to Philadelphia, passing unchallenged through Aquia Landing. They reached Philadelphia—and freedom—on Christmas day 1848.

The opening of the rail line to Aquia in 1842 provided opportunity for slaves seeking freedom. In 1848, slaves William and Ellen Craft of Georgia embarked on their dangerous journey to escape. Ellen, born of a slave mother and white father disguised herself as white man seeking medical treatment in the north. William assumed the treatment in the North. William assumed the role of her body servant. They traveled by train, carriage, and steamship from Georgia to Philadelphia, passing unchallenged through Aquia Landing. They reached Philadelphia—and freedom—on Christmas day 1848.

Three months later, Henry “Box” Brown became one of the most famous fugitives in American history. A slave in Richmond, Brown packed himself in a wooden box to be mailed to freedom. By wagon, train, and steamboat, Brown traveled north, sometimes upside down. After 27 hours and undetected passage through Aquia Landing, the Express Mail box carrying Henry Box Brown was delivered in Philadelphia, its occupant a slave no more.

Gateway to Freedom

During the Civil War, most white Stafford residents greeted the arrival of the Union army in April 1862 with outrage and fear. But many slaves throughout the region rejoiced at the opportunity for freedom. Thousands left their houses, farms, and plantations, heading north toward the Union army.

During the Civil War, most white Stafford residents greeted the arrival of the Union army in April 1862 with outrage and fear. But many slaves throughout the region rejoiced at the opportunity for freedom. Thousands left their houses, farms, and plantations, heading north toward the Union army.

Some “contrabands” (as the army called them), took jobs with the Union army, often as paid servants to officers. They earned between 25 and 40 cents per day, plus a ration. But for most former slaves, their journey to freedom continued to and culminated at Aquia Landing. Soldiers shepherded them onto steamboats for the short journey up the Potomac to Washington, D.C.

When the Union army evacuated the area in September 1862, a final burst of freedom-seekers flooded Aquia Landing. Among them was Fredericksburg slave John Washington, who slipped aboard the Washington-bound steamer Keyport (above). That spring and summer, as many as 10,000 slaves made the journey into Union lines—to freedom.

Related Links